Gauss’ law for electrostatics

Read Tipler and Mosca (2004) chapters 21 and 22

(The electric field I and II); Pelcovits and Farkas (2024) chapter 11

(Gauss’s law). See also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zu2gomaDqnM

Gauss’s law

Electric flux

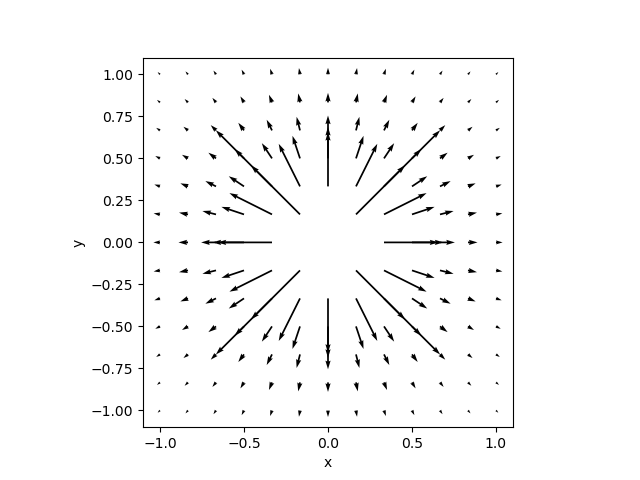

The flux of a vector field is a quantity that reflects how much of the field is passing through an area. The fourth equation on the AP Physics C Electricity & Magnetism equation sheet gives the electric flux: \[\Phi_E = \iint \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{A}.\qquad{(1)}\]

In eq. 1, the notation \(d\vec{A}\)

means \(\hat{n} dA\), where \(\hat{n}\) is the normal to \(dA\), so that the fluxfrom fluxus, from Latin, fluere, “to

flow”

quantifies how much field is flowing through the area,

normal to it. The dot product with the normal means we do not count

stuff passing parallel to the area, which doesn’t really flow through

it. We will see similar fluxes for magnetic fields and current. Flux

also occurs in other fields like heat and mass transfer, nuclear reactor

theory, fluid mechanics, and more.

The \(\iint dA\) notation means we

are doing a double integralYou probably are not yet doing these in your

multivariate calculus class, but you will. Typical applications of

double integrals are to find areas (\(\iint

dA\)), moments of area (\(\iint r^2

dA\)), surface areas, cumulative probabilities under multivariate

pdfs, etc. There are also triple integrals, often used to find volumes

(e.g. \(\iiint dV\)).

over an area. You are used to doing a single integral,

e.g. \(\int dx\). A double integral

could be the integral of an integrand that itself is an integral, such

as \(\int \int dx dy\), perhaps

rewritten as \(\iint dA\) to be less

cumbersome. Sometimes, in the interest of writing quickly, we may write

\(\int dA\), recognizing it as a double

integral because it is with respect to \(dA\).

Integral form of Gauss Law

Gauss’s lawDeveloped some by Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1773; mainly

by Carl Freidrich Gauss in 1835. See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gauss\%27s_law. Gauss’s

law is the first of four Maxwell’s Equations which

describe electromagnetic fields; we’ll get to the other three

later.

relates the electric flux out of an arbitrary closed

contour to the charge enclosed (\(q_{enc}\)) within the countour: \[\begin{aligned}

\oiint \vec{E}\cdot d\vec{A} &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\

&= \dfrac{1}{\epsilon_0} q_{enc}

\end{aligned}\qquad{(2)}\]

The notation \(\oiint d\vec{A}\) means the flux is taken over a closed contour. The contour can be any conveniently chosen shape so long as it has no holes and doesn’t leak. You could choose to integrate over the surface of a potato shape; more often however, the contour is a well-chosen sphere or cylinder.

In eq. 2, \(q_{enc}\) is the charge enclosed within the contour. The actual distribution of the charge within the contour does not really matter for application of eq. 2.

Gauss’s law is a bit funny in that it doesn’t work directly with

\(\vec{E}\) but rather it is a

statement about the double integral of \(\vec{E}\) over some closed contour. At

first sight, these would seem to leave us worse off by adding all kinds

of confusing advanced math to the stuff we must think about. In

practice, however, we can sneak around the advanced math by

making wise choices of the closed contour we integrate over, turning the

multivariate calculus into a geometry problemIn 6.003 Signals and Systems, MIT EECS Prof Stephen

Senturia used to say “We don’t want to do math! We suck at math! We make

stupid mistakes when we try to do math!” suggesting we should find

clever ways to get around actually doing the math. Compare to Chinese

warrior philosopher Sun Tzu (544-496 BCE), “The supreme art of war is to

subdue the enemy without fighting.” Checkmate.

.

For now, we will start using Gauss’s law without deriving it. Gauss’s law can be developed from Coulomb’s law using some multivariate calculus sleight of hand and the sifting properties of the Dirac delta function, but we will not yet go there because you have yet to get to these in your multivariate calculus class.

Differential form of Gauss’s Law (optional aside)

eq. 2 is the integral form of Gauss’s law; there is also a

differential form: \[\vec{\nabla}\cdot\vec{E}=\dfrac{\rho}{\epsilon_0}.\qquad{(3)}\]

The differential form is often put on t-shirts at fancy engineering

schools but is not in any way testable in AP Physics C

Electricity and MagnetismIt is mentioned here merely for those of you who love

seeing odd math and new math symbols so much that it makes you want to

go out and know what the heck these things mean… You may see this in an

physics (e.g. 8.022) or multivariate calculus (e.g. 18.023) class next

year.

.

While the integral form is useful when symmetry and geometry in the

problem allows us to pick a convenient contour, the differential form is

more usable otherwise. The fancy \(\vec{\nabla}\cdot\vec{E}\) notation means

the divergence of \(\vec{E}\), a multivariate calculus

operation that works kind of like our flux calculation as we shrink our

closed contour to be very tiny. There are several multivariate calculus

theorems that become useful when relating such quantities to path, area,

and volume integrals which they will go over later. The upside-down

triangle\(\vec{\nabla}\) is

typically spoken as “del”

\(\vec{\nabla}\) is a

multivariate differential calculus vector operator given in Cartesian

coordinates by \[\vec{\nabla}=\dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}\hat{i}

+ \dfrac{\partial}{\partial y}\hat{j} + \dfrac{\partial}{\partial

z}\hat{k}.\]

Gauss’s law solution for a point charge

{#fig:gausslawpoint}

To illustrate the utility of eq. 2 let us first find the

electric field for a point charge \(Q\)

at the origin. We select as a contour a sphere of radius \(r\) centered at the origin.

\[\oiint_{\text{sphere}} \vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a} = 4\pi k Q.\qquad{(4)}\]

Based on symmetry, the \(\vec{E}\) field must point radially everywhere and should only depend on \(r\). Also, the normal to our chosen sphere contour also point radially. These simplify the integral in the left hand side of eq. 4 considerably, allowing us to ditch the dot product and pull \(|\vec{E}|\) out of the integral. \[|\vec{E}| \oiint_\text{sphere} da = 4\pi k Q.\]

The integral over the sphere of \(da\) is just the area of the sphere (\(A=4\pi r^2\)), so that \[\begin{aligned} |\vec{E}| 4\pi r^2 &= 4\pi k Q \\ |\vec{E}| &= \dfrac{kQ}{r^2} \\ \vec{E}(r) &= \dfrac{kQ}{r^2} \hat{r}=\dfrac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\dfrac{Q}{r^2}\hat{r}. \end{aligned}\qquad{(5)}\] which matches what we got from Coulomb’s Law force divided by (test) charge. The final step in eq. 5 recognizes that we used symmetry to conclude the electric field must point radially.

Gauss law solution for an infinite line charge with charge density \(\lambda\)

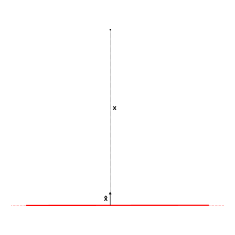

{#fig:gausslawline} Gauss’s law contour for electric

field from a line charge of charge density \(\lambda \unit{\coulomb\per\meter}\).

Consider an infinite line charge of charge density \(\lambda\) C m−1 distributed

along its length. Previously, we developed an expression for the

electric field by breaking the line charge into small \(dq\), finding the small contributions \(d\vec{E}\) to the electric field, and

integrating them all. It required trig substitution and got sort of

ugly.

Our approach here using Gauss’s law will be:

Select a contour that exploits symmetry and geometry of the problem. In this problem, we pick a cylinder of radius \(r\) and length \(l\), concentric with the line charge, allowing \(l\) to grow big if we want.

For a well-chosen contour, stuff should pull out of the Gauss’s law integral, changing the multivariate calculus problem to geometry. We will need that the area of a cylinder is \(A=2\pi r l\).

We also note that the cylinder endcaps’ normals \(\hat{n}\) point in the \(\pm z\) direction, while due to symmetry the electric field must point in the \(r\) direction, perpendicuar to \(\hat{n}\). Due to the dot product, the endcaps’ contribution to \(\oiint \cancelto{0}{\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a}}\) is zero.

Use the charge density to find \(q_{enc}\), i.e. \(q_{enc}=\lambda l\).

Simplify. Have a cup of Earl Grey teaA black tea blend flavored with oil of bergamot (Citrus bergamia), possibly associated with Charles, 2nd Earl Grey; and with fictional Captain Jean-Luc Picard from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Tea of choice of nerds everywhere. See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earl_Grey_tea

in the time saved compared to doing the line integral. Tea of choice of nerds everywhere.

\[\begin{aligned} \oiint\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a} &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| \iint_\text{cylinder} da &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\cancel{\pi} r \cancel{l} &= 4\cancel{\pi} k \lambda \cancel{l} \\ |\vec{E}| &= 2 k \lambda \dfrac{1}{r} \\ \vec{E}(r) &= 2 k \lambda \dfrac{1}{r} \hat{r}=\dfrac{\lambda}{2\pi\epsilon_0}\dfrac{1}{r}\hat{r}. \end{aligned}\]

Gauss’s law solution for a plane with charge density \(\sigma\)

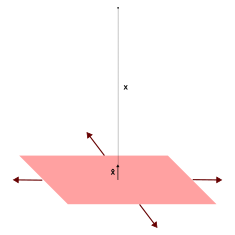

{#fig:gausslawplane} Gauss’s law contour for electric

field for a plane of charge density \(\sigma

\unit{\coulomb\per\meter\squared}\).

Consider an \(xy\) plane

with charge density \(\sigma\)

C m−2 distributed over its surface. We choose a contour

consisting of a cylinder with long axis along the \(z\) axis, with the plane passing through

its middle. We allow the cylinder radius to be as large as we like. By

symmetry the field must point away from the plane in the \(\pm z\) direction, so that the only

contributions in the Gauss’s law integral are from the endcaps of the

cylinder. Application of Gauss’s law proceeds in a straightforward

manner:

\[\begin{aligned} \oiint\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a} &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2 \iint_\text{ends} da &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2 \pi r^2 &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2 \cancel{\pi r^2} &= 4\pi k \sigma \cancel{\pi r^2} \\ |\vec{E}| &= 2\pi k \sigma\\ \vec{E}(z) &= \begin{cases} 2\pi k \sigma \hat{z} = \dfrac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0} \hat{z} & z \geq 0 \\ -2\pi k \sigma \hat{z} = -\dfrac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0} \hat{z} & z<0 \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Gauss’s law solutions for cylinders of radius \(R\)

Thin cylindrical shell with charge density \(\sigma\)

We choose a cylindrical contour of radius \(r\). There are two solutions.

Where \(r<R\), \(q_{enc}=0\) so by inspection \(\vec{E}=0\) for \(r<R\).

Where \(r>R\), the solution

should look just like our line charge solutionIn physics, it is nice to turn a problem into one you

already know how to do.

, with \(\lambda = \sigma 2\pi

R\); but let’s do it out anyway.

\[\begin{aligned} \oiint\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a} &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| \iint_\text{cylinder} da &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k \sigma 2\pi R l \\ |\vec{E}| &= 4\pi k \sigma \dfrac{R}{r} \\ \vec{E}(r) &= \begin{cases} 0 & r < R \\ 4\pi k \sigma R \dfrac{1}{r} \hat{r} = \dfrac{\sigma R}{\epsilon_0} \dfrac{1}{r} \hat{r} & r \geq R \end{cases} \end{aligned}\]

Solid cylinder with charge density \(\rho\)

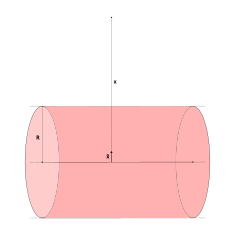

{#fig:gausslawsolidcylinder} Gauss’s law contour for

electric field for a solid cylinder with charge density \(\rho \unit{\coulomb\per\meter\cubed}\).

For a solid cylinder of radius \(R\) with charge density \(\rho\) C m−3, the solution for

\(r>R\) should look identical to the

solutions for a line charge (\(\lambda=\pi R^2

\rho\)) or a cylindrical shell (\(\sigma = \frac{R}{2}\rho\)).

\[\begin{aligned} \oiint\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a} &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| \iint_\text{cylinder} da &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k \rho \pi R^2 l \\ |\vec{E}| &= 2\pi k \rho \dfrac{R^2}{r} \\ \end{aligned}\]

For \(r<R\), inside the solid cylinder, \[\begin{aligned} \oiint\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{a} &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| \iint_\text{cylinder} da &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k q_{enc} \\ |\vec{E}| 2\pi r l &= 4\pi k \rho \pi r^2 l \\ |\vec{E}| &= 2\pi k \rho r \\ \end{aligned}\]

The electric field is \[\vec{E}(r) = \begin{cases} 2\pi k \rho r \hat{r} & r < R \\ 2\pi k \rho R^2 \dfrac{1}{r} \hat{r} & r \geq R \end{cases}\]

Gauss’s law solutions for spheres of radius \(R\)

We remind ourselves that for a sphere of radius \(R\), \(A = 4\pi R^2\) and \(V=\frac{4}{3}\pi R^3\).

Thin spherical shell with charge density \(\sigma\)

{#fig:gausslawsphericalshell} Gauss’s law contour for

electric field for a thin spherical shell with charge density \(\sigma \unit{\coulomb\per\meter\squared}\).

Choose a Gauss’s law contour that is a concentric sphere

of radius \(r\). Where \(r>R\) the solution will look like a

point charge with \(Q=\sigma 4\pi

R^2\). Inside the spherical shell, \(q_{enc}=0\) so by inspection \(\vec{E}=0\) for \(r<R\).

\[\vec{E}(r) = \begin{cases} 0 & r < R \\ \dfrac{4 \pi R^2 \sigma k}{r^2}\hat{r} & r \geq R \end{cases}\]

Solid sphere \(\rho\)

{#fig:gausslawsphere} Gauss’s law contour for

electric field for a solid sphere with charge density \(\rho \unit{\coulomb\per\meter\cubed}\).

It is left as an exercise for the student to show

that

\[\vec{E}(r) = \begin{cases} \dfrac{4 \pi \rho k}{3} r \hat{r} & r < R \\ \dfrac{4 \pi R^3 \rho k}{3 r^2}\hat{r} & r \geq R \end{cases}\]

See also

MIT 8.02 Walter Lewin video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zu2gomaDqnM

The Mechanical Universe electric field video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wq9TjQZDrAA